Most of this website is devoted to Pauline Boty herself of course, but here we take the opportunity to talk to art historian, curator and author Sue Tate, who has been so instrumental in bringing Boty’s life and work to a wider audience.

PaulineBoty.org: Thank you for taking the time out to talk with us today.

Sue Tate: It’s an absolute pleasure. I’m always more than happy to discuss all things Boty-related with people!

PBO: Why did you choose to become an art historian?

ST: I’ve always been fascinated by art history. It’s a wonderful subject. You get the chance to enjoy beautiful, fascinating, sometimes tough, always creative works of art and to explore and understand them in their wider historic, and social context. It’s such an endlessly fascinating and rewarding combination.

PBO: How did you come across Pauline Boty and why did she interest you?

ST: Well, it all started in 1991 when I visited a huge exhibition of Pop Art at the Royal Academy. There were plenty of images of women, yet out of 202 works of art only one was by a woman. I thought, surely women artists had something to say about popular culture, Pop’s source material. It addressed them so directly as consumers not only of things but also of pop experiences – fashion, music etc. – and of course they had plenty to contribute. As soon as you looked properly, there they were, making names for themselves at the time – Idelle Weber, Jann Haworth, Evelyn Axell and Marisol and many more – only to later be marginalised or even excluded from the story of Pop altogether. I needed a topic for my MA dissertation and this was it.

Then, in 1993, David Alan Mellor sought out and discovered lost works by Pauline Boty on her brother’s farm and showed some at a big exhibition, The Sixties Art Scene in London, at the Barbican. It was the first time her work had been seen in public for nearly 30 years, since her tragically early death from cancer in 1966 aged only 28. She was one of the founders of British Pop art and it was such stunning, interesting and vibrant work – yet she had been lost to sight. I was hooked and decided to make her my case study, David Mellor kindly shared his contacts and I was off on a thrilling journey of discovery.

It was such stunning, interesting and vibrant work yet she had been lost to sight. I was hooked and decided to make her my case study.

PBO: So how and what did you discover?

ST: Bridget Boty, Pauline’s sister-in-law, very generously welcomed me at the farm, and showed me paintings and collages, family documents, photo albums, newspaper cuttings and more. Pauline’s brothers were equally helpful sharing sketchbooks and other works and their fascinating memories of childhood and adolescence.

I tracked down and had wonderful conversations with Pauline’s friends and colleagues, people like Derek Boshier, Celia Birtwell, Caroline Coon and many others. More and more I came to see what an amazingly charismatic, vivacious, talented, innovative and brave person she was – smashing stereotypes and taking on issues well ahead of their time.

Various clues led me to more works, unseen in the public for at least three decades. For example it was so exciting to find Portrait of Derek Marlowe with Unknown Ladies in a farmhouse kitchen in Sussex and BUM in a lock up in the basement of mansion flats in London, all tangled up in a heap of furniture. Both have since sold for six figure sums!

PBO: What did you then do with all your research?

ST: Well, firstly it was important to me to make my work accessible. So, with the help of Althea Greenan at the Women’s Art Library, we got an Arts Council grant to have it all professionally photographed and logged at the Library and with the Arts Council. The resultant transparencies and slides have been an ongoing resource for other researchers and students since.

Then, in 1998, two London commercial art galleries – the Mayor Gallery and Whitford Fine Art – put on a full exhibition of Boty’s work that I helped to curate. They kindly let me include works that were not for sale but which really enhanced the show, and it was just so great to see most of Boty’s oeuvre all together for the first time in decades. As a result Tate bought their first work at this point – The Only Blonde In The World – later adding Derek Marlowe with Unknown Ladies to their collection.

Then I’ve done all those scholarly things that help make a difference to the reception of an artist – given papers at art history conferences, written catalogue essays and chapters in books and given talks at auction houses and galleries in the UK, Europe and the USA.

In 2009-10 an award winning, game changing exhibition of women Pop artists – Seductive Subversions – toured the USA with a compendious book. Gallerists and curators could no longer say they didn’t know of the women in Pop! I was so happy to collaborate on this show – arranging for Boty’s work to be included, writing for the book, giving talks.

More and more I came to see what an amazingly charismatic, vivacious, talented, innovative and brave person she was – smashing stereotypes and taking on issues well ahead of their time.

PBO: And how did the exhibition you curated and accompanying book come about?

ST: Ah yes – that’s important. Wolverhampton Art Gallery bought a major work – Colour Her Gone – and they invited me to curate a full, in-depth retrospective in 2013, Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, the first in a public gallery. It travelled to Pallant House Gallery and on to Muzeum Sztuki in Poland. Both UK venues also drew art-lovers from London and elsewhere in the country and there was by now a real media buzz.

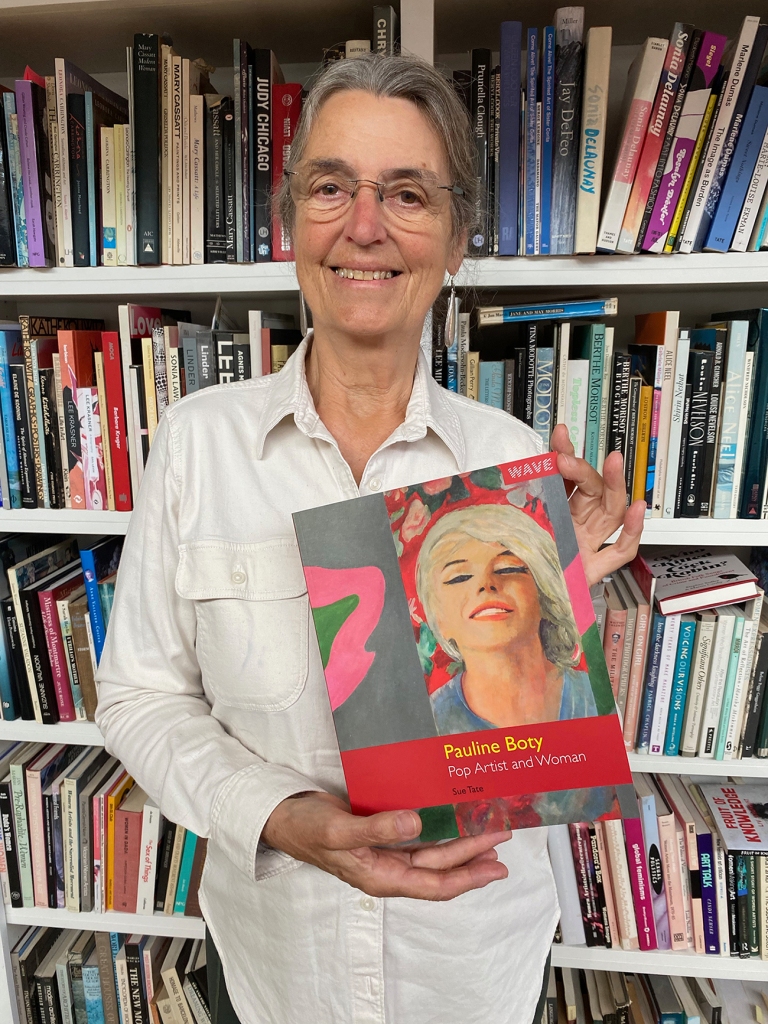

And I’m delighted to say that the richly illustrated book I wrote to go with the show, funded by the Paul Mellon Foundation, has been very well received and contributed to both the art historical and market value for Boty’s work. Honestly – it’s been such an amazing journey over the years as Boty and her work gradually came to be seen and understood.

PBO: How would you describe her work as being different from that of her peers?

ST: What we have to remember is that mass culture was very gendered and Pop Art has, until more recently, been male dominated. So, Pauline Boty and other women Pop artists enrich Pop by contributing a female take – so different from her male peers but belonging to a cohort of women artists.

So we see Boty in works like 5-4-3-2-1 exploring female sexuality, from the inside as it were – the subjective experience – celebrating the pleasures of dancing to the latest pop music and anticipating what might be next. “Oh for a Fu…” declares a banner on its right – really outrageous stuff, especially for a young woman. Two years later when Kenneth Tynan said the F-word on TV questions were asked in the House of Commons!

She reversed the usual direction of “the gaze”, gleefully turning her desiring eye on male objects of desire – most notably in With Love to Jean Paul Belmondo, who she described as “the dish with the ravey navel”. And other works are critical too – she is in no way oblivious to the problems for women negotiating mass culture – and paintings like It’s A Man’s World I and II are overtly feminist.

She was also politically aware and commented on current events in, for example, Count down To Violence. The war in Vietnam, the assassination of Kennedy, the race riots in Alabama are all represented – but she critiques these things as a woman – in the centre of the painting a manicured hand descends, wielding secateurs to sever a red rose, Boty’s symbol of female pleasure.

And she was remarkably well read, so there is an unusually rich cultural mix in her work: Proust and Marilyn Monroe, Baudelaire and Elvis, Einstein and the Beatles, all rubbing shoulders together.

PBO: Do you have any theories on where the missing works might be?

ST: That’s a very good question! Of course Scandal 63 (about the Profumo Affair that brought down the Conservative government) is the one we would really love to locate. We know that it was commissioned by a “Mr Wright” who wished to remain anonymous, and we have good colour photographs by Michael Ward of Boty holding this fabulous painting – dominated by Christine Keeler in that iconic pose. A young researcher, Tom Glover, put in a huge amount of work into trying to find it but to no avail.

July 26 is another lost work, about the Cuban revolution. Again, it’s known from photographs and can also be glimpsed in a black and white documentary from the 70s on left wing activism. It’s on the wall of the offices of Black Dwarf, a revolutionary magazine co-founded by Boty’s widower, Clive Goodwin – but hasn’t been seen since. Perhaps these works are lost for good or perhaps one day they will turn up. We can live in hope!

PBO: Why do you think her work was overlooked for so many years?

ST: I think her work from a female perspective really challenged the almost exclusively male version of Pop. When women were all but missing from the Royal Academy show in 1991, the only explanation given at the time was that women lacked the necessary “detachment” – a cool distancing seen as imperative to belonging in the Pop stable. Boty’s work was too subjective – getting into, or expressing, the lived experience of being a fan or of occupying a female body.

She also smashed gender stereotypes – demanding the right to be both a fully sexual being and an intellectual, talented and ambitious artist. While this was fine for men, at the time these things were mutually exclusive for women and just couldn’t be reconciled – you had to be one or the other. So, when she posed naked in high libertarian spirits with her work, or made a living as an actress onstage and screen, her reception as an artist was damaged – she was reduced to the sexy girl/starlet in the media.

It has been argued that her early death was a reason for her disappearance, yet she lives so vividly in the memories of those who knew her. And – young, beautiful and dead – surely, like James Dean, she should have achieved iconic status! Of course, things have changed. Pop has relaxed its insistence on “detachment” making room for women’s work. And now with developments in feminism, Boty’s attempt to be valued, to be seen as a whole person, really resonates.

PBO: And how have things developed in the last 10 years?

ST: Boty is now routinely included in art historical publications and group exhibitions of Pop around the world and is garnering more and more attention – including a documentary film currently in production from Mono Media. And right now two works feature in important displays at Tate in London – both Tate Modern and Britain.

Sale prices have accelerated steeply too. The turning point was in 2016 when BUM sold for £632,750 at Christie’s. And last year, 2022, With Love to Jean Paul Belmondo hit the million pound mark at Sotheby’s. Of course market value is not the same as aesthetic value but it is a measure of visibility and what is so pleasing is the way in which her work is now really understood, valued and is reaching an ever wider audience.

Her work and life explore, celebrate and critique experiences of popular culture – both the pleasures to be found and the problems it throws up … Boty’s life and work have incredible relevance today, speaking to a current generation.

PBO: What do you feel Boty’s legacy has been/will be?

ST: I know it’s rather a cliche but she really was ahead of her time. Her friend, Jennifer Carey, believed she aimed “to re-establish the kind of a woman one could be”. She brings a fresh female voice to Pop making it so very much richer and more meaningful. Her work and life explore, celebrate and critique experiences of popular culture – both the pleasures to be found and the problems it throws up – especially for women. In holding both celebration and critique together, Boty’s life and work have incredible relevance today, speaking to a current generation.

PBO: Looking back over the journey what are your thoughts?

ST: It has been just amazing, and a privilege, to have played an active part of this journey from near obscurity to a place where Pauline Boty’s work is properly valued, with a secure place in art history.

PBO: Do you have any further Boty-related projects planned?

ST: I do! Firstly there is an exciting exhibition coming up in the UK that I am collaborating on. And with Christopher Gregory, the host of this website, we are close to completing a detailed inventory of all Boty’s work we intend to make available to curators, researchers and gallerists and are in discussions about developing a full catalogue raisonné.

And, most excitingly of all, Thames and Hudson have just commissioned me to write a fuller, definitive book on Boty, to be titled Pauline Boty – Art, Life and Times. My writing is already underway and it’s due out in 2026.

PBO: Many thanks for taking the time to talk with us and please keep us posted on the progress of your new projects!

ST: It’s been a pleasure!

.

Sue Tate’s book, “Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman” is available at Amazon [link] and eBay [link]